Alvin Tjitrowirjo is an established designer and the founder of alvinT, a design studio based in Jakarta, Indonesia. His brand has garnered international acclaim, with his works being showcased at hailed design fairs and exhibitions around the world, including Milan, Paris, and Singapore. With a deep connection to his cultural heritage and a passion for creating meaningful, purpose-driven designs, Alvin has earned a reputation for blending traditional craftsmanship with modern design sensibilities. His work often reflects a strong sense of spirituality, cultural narratives, and sustainability, making him a distinctive voice in the global design scene. In an interview with Asia Designers Directory, Alvin introduced his latest creation and discussed his motivations towards preserving traditional Indonesian designs through his work.

Can you tell us about your latest creation and the inspiration behind it?

Our latest creation, Jiwa, responds to the spiritual value of craft, which has always been deeply intertwined or inseparable with the act of creation. In Indonesia, where tradition and culture are so closely tied, many people use craft as a way to express their awe toward forces beyond their understanding. This creates a complex relationship between the maker, the object, and the wisdom derived from it. Craft is not just about creation; it expresses something greater.

The process of making craft often involves a deep understanding of the materials—knowing which to pick, the right time to harvest, and how seasons and the surrounding environment influence the outcome. This knowledge is passed down through generations, making it more than just an object—it is a reflection of the connection between the maker and the world around them.

- Jiwa seeks to create meaningful connections between us and the world. (Photo credit: Christopher Octaviano)

In contrast, modern craft-making is often systematic, efficient, and driven by commercial value. While efficiency is important, modern production often loses the wisdom and connection to nature that traditional craftsmanship embodies. This is a concern, as certain objects can easily be reduced to their monetary value, losing their deeper, spiritual significance.

The inspiration for this piece comes from the altars found in many Chinese families. Though made of simple materials, these altars act as a portal, connecting humans with the spiritual world. Given the current state of the world, with environmental destruction and a lack of care for both nature and each other, I felt it was important to create something that serves as a gateway and reminder for people to reconnect with nature.

The legs of Jiwa are intentionally designed to evoke the legs of animals, while the curving part of the shelves resembles the roof of temples or sacred spaces, symbolising a deep cultural connection to the earth. We hope to remind people of the importance of re-engaging with nature in a more meaningful way. Understanding nature scientifically is important, but it is also essential to approach it from different perspectives and values. Ultimately, we cannot live without nature. The rice symbolised in the piece is a reminder that, just as we honour our ancestors with offerings, perhaps it is time to not only pray for nature but to restore our connection with it.

What can Indonesian designers learn from global designers, and what unique elements of Indonesian design do you they should preserve and highlight?

One of the key lessons we can learn from the global design scene is the power of imagination. This imagination is not just about the shapes we can turn craft into, but about envisioning what role Indonesia can play on the global stage.

What is the future for designers from countries with a deep connection to culture and tradition? How should they position themselves on the global stage? These are the bigger questions we need to ask.

I also believe we are still grappling with a post-colonial mindset, where there is somewhat a sense of inferiority that we need to overcome. Another challenge we face is Indonesia’s struggle to define what Indonesian design truly is. With 17,000 islands, 700 languages, and countless dialects and subcultures, design should not be confined by national boundaries. Instead, it should reflect the relationship between people, places, and the culture that unites them. Perhaps we can also liberate ourselves into not just identifying ourselves just simply as one country in terms of a visual or a design identity, but we can move beyond that.

- The Dahan bench aims to connect with materials and the environment, while exploring our identity, present moment, and creative goals.

Can you share some of your most recent partnerships and collaborations, and how these projects align with your vision for the brand?

Two years ago, we collaborated with an indigenous community in central Borneo. They are some of the finest rattan weavers I have ever seen, but at the same time, they are threatened by modernisation. The younger generation lacks pride in their craft and does not see a future in becoming a weaver. This triggered something in me and turned into a calling. As a designer, I feel I should play a significant role in this.

Throughout the years, I was taught to design products that sell. That is the role of a designer in an industrial setting. But now I realise that there are bigger and more complex issues. If we continue designing products that sell while disconnecting people from their culture and nature, we are not solving the problem.

That was a big milestone for us. We realised that with the pieces we create, we need to have a stronger intention. We must understand the complexity of social, economic, and cultural problems, and we need to unlearn many things, including the need to break away from the Indonesian design language or identity.

I believe there have been many breakthroughs in terms of our thinking. Now, it’s a matter of putting those ideas into practice, and hopefully, that can steer the industry toward a better trajectory.

- Ndare Collection explores the relationship between the artisan, the environment, and culture. (Photo credit: Martin Westlake)

- Ndare weavers (Photo credit: Dodik Cahyendra)

Can you share some key milestones AlvinT has reached since its inception? How have these moments shaped the growth and direction of the studio and what are your aspirations for the future?

Being in business for 18 years has been quite a rollercoaster because it is challenging understanding the market, as well as understanding myself as a designer and what I want to do in the industry. I believe that by having our shops open and close, and at the same time showcasing our pieces on the global stage—whether in Milan, Paris, or other parts of the world—we get a clearer picture of where we stand and what we need to do next.

Countries like Indonesia, Singapore, and other Southeast Asian nations serve as gatekeepers of traditional culture. These treasures are the essence of who we are and an integral part of our identity.

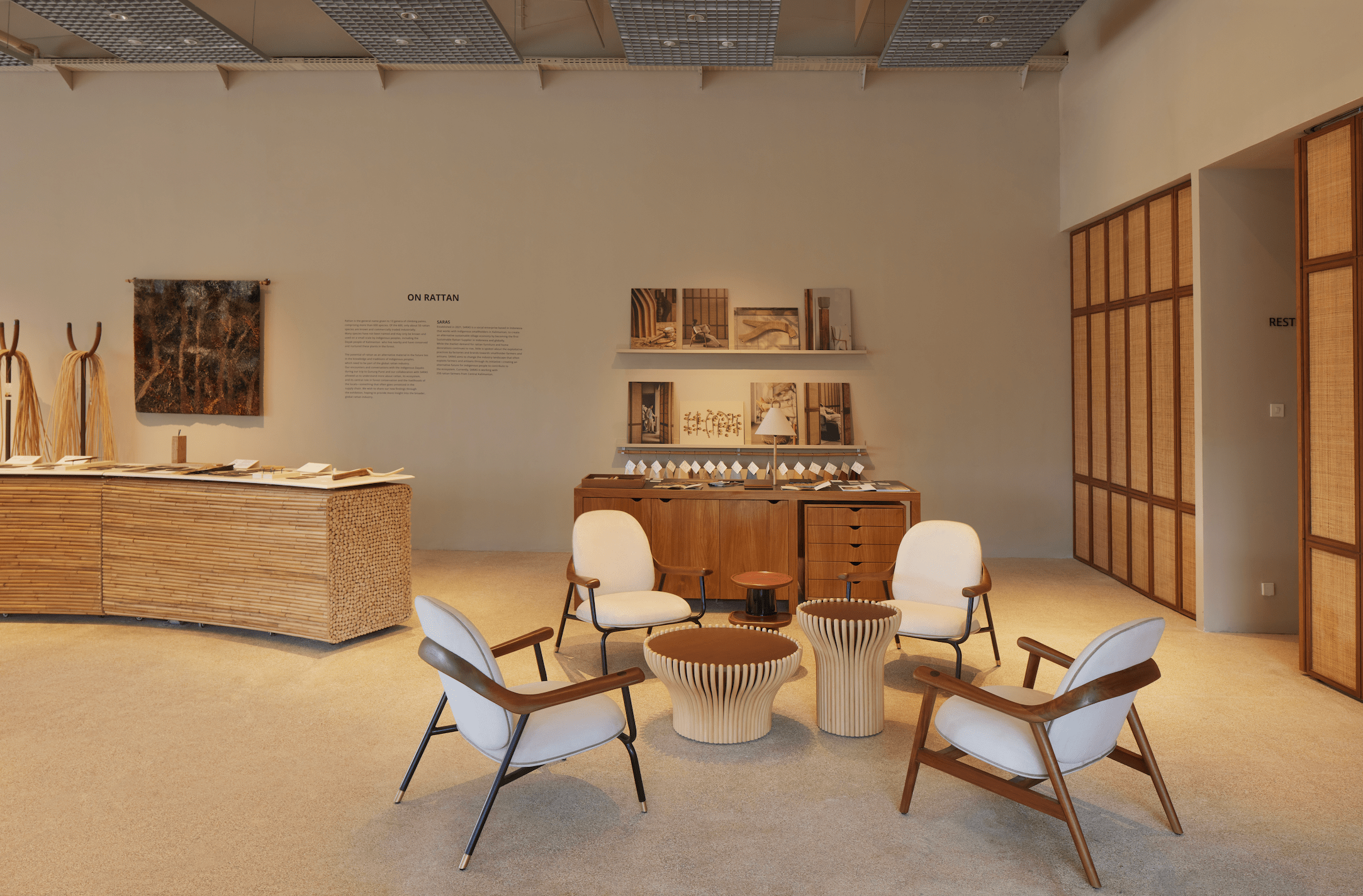

We recently opened a gallery in Jakarta, located in Indonesia Design District (IDD). The gallery serves as an experiential space where we aim to showcase the insights and wisdom we’ve discovered from traditional communities. The gallery also acts as a bridge, translating these traditions for modern people living in big cities, helping them understand and appreciate the value of this knowledge. Our broader goal is to foster collaboration and raise awareness around this cause.

I believe a big shift is already underway. As people become more aware of climate change and the need to live sustainably, there is also growing recognition that we can learn from the past, especially from traditional cultures. It’s going to be very interesting, and I’m also eager to explore the other roles I need to take on. So far, I’ve been wearing different hats, and I think that’s essential if we are to truly address the bigger challenges ahead.

- New alvinT Studio in Jakarta (Photo credit: Martin Westlake)